Get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

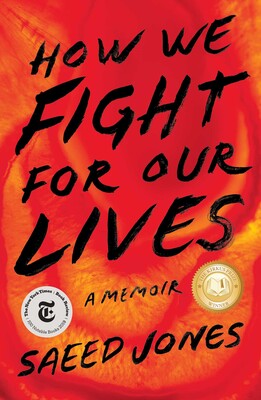

About The Book

One of the best books of the year as selected by The New York Times; The Washington Post; NPR; Time; The New Yorker; O, The Oprah Magazine; Harper’s Bazaar; Elle; BuzzFeed; Goodreads; and many more.

“People don’t just happen,” writes Saeed Jones. “We sacrifice former versions of ourselves. We sacrifice the people who dared to raise us. The ‘I’ it seems doesn’t exist until we are able to say, ‘I am no longer yours.’”

Haunted and haunting, How We Fight for Our Lives is a stunning coming-of-age memoir about a young, black, gay man from the South as he fights to carve out a place for himself, within his family, within his country, within his own hopes, desires, and fears. Through a series of vignettes that chart a course across the American landscape, Jones draws readers into his boyhood and adolescence—into tumultuous relationships with his family, into passing flings with lovers, friends, and strangers. Each piece builds into a larger examination of race and queerness, power and vulnerability, love and grief: a portrait of what we all do for one another—and to one another—as we fight to become ourselves.

An award-winning poet, Jones has developed a style that’s as beautiful as it is powerful—a voice that’s by turns a river, a blues, and a nightscape set ablaze. How We Fight for Our Lives is a one-of-a-kind memoir and a book that cements Saeed Jones as an essential writer for our time.

Excerpt

The waxy-faced weatherman on Channel 8 said we had been above 90 degrees for ten days in a row. Day after day of my T-shirt sticking to the sweat on my lower back, the smell of insect repellant gone slick with sunscreen, the air droning with the hum of cicadas, dead yellow grass cracking under every footstep, asphalt bubbling on the roads. It didn’t occur to me to be nervous about the occasional wall of white smoke on the horizon that summer. Everything already looked like it was scorched, dead, or well on its way.

I was twelve years old and I had just finished the sixth grade. Most days, after Mom headed to her job at the airport, I would stay inside our apartment, stationed by the window. Cody and his younger brother, Sam, two white boys who lived a few apartment buildings over from us, were always playing catch in the parking lot, though I never joined them. I wasn’t good at throwing the ball and it was too hot for me to go out and pretend.

When I wasn’t at my perch, acting like I wasn’t watching them, I would flip through Mom’s old paperback books. So far, I had tried out Tar Baby and The Color Purple, both unsuccessfully. Toni Morrison’s sentences were like rivers with murky bottoms. They didn’t obey the rules I was learning in school. When I stepped in, I couldn’t see my feet; I retreated back to the shore. Alice Walker lost me because, a few pages in, some girl was talking about the color of her pussy. I figured the book didn’t have much more to offer me after that.

Today I tried again. I picked up a worn copy of Another Country by James Baldwin, sat down cross-legged on the floor, and started reading. A sad man walks through the streets of New York City late one winter night. He goes into a jazz club looking for someone or something but doesn’t say why.

Minutes pooled into hours. Black people sleeping with white people. Men kissing men, then kissing women, then kissing men again. Every few pages, I would look up from the book and peek at our apartment’s front door. Mom wasn’t home from work yet and I felt like I would get in trouble if she saw me reading this book. I went into my bedroom, with our cocker spaniel, Kingsley, trailing behind me, and I closed the door.

The novel turned me on. I didn’t know books were capable of anything like this. Until now, I had liked reading but it was just something you did. A good thing, like drinking water on a hot day, but nothing special. Holding Another Country in my hands, I felt that the book was actually holding me. Sad, sexy, and reeking of jazz, the story had its arm around my waist. I could walk right into the scene, take off my clothes, and join one of the couples in bed. I could taste their tongues.

About a third of the way into the novel, I found a Polaroid tucked between the pages like a bookmark. It was a picture of a man I had never seen before. He didn’t resemble anyone in my family, but, for all I knew, he could have been a distant cousin or uncle. He was leaning against a sedan with his arms crossed and an odd smile on his face, as if the person holding the camera had just told him an inside joke. Or maybe this man was doing the telling. The smile felt intimate, inappropriate, like a hand sliding down where it should not be.

Someone had written “Jackson, Mississippi, 1982” on the back, but I could’ve figured that out on my own. The man was dressed like an extra in a Michael Jackson video. He had on a knit sweater and black, acid-washed jeans that were way too tight. I could see the whites of his socks. And I knew he was in Mississippi because of the red dust all over his sneakers. On a trip to Mississippi with my aunt once, I’d seen that dirty redness on every car, lapping at the sides of houses like flood tides, and all over the loafers I was wearing. “That’s what Mississippi does to you,” my aunt had said when she saw my shoes. I kept on trying to use one foot to brush red dirt off the other, only making things worse.

I decided I didn’t like the man in the picture. The dirt on his shoes irritated me, and the longer I looked at his smile, the more I felt like he was looking directly at me. Not at the camera in 1982, but at me, sixteen years later. He grinned like he knew something about me, a punch line I hadn’t figured out yet.

When Mom came home from work, she headed straight into the kitchen to pour herself a glass of water from the Ozark jug. That was part of her routine. She’d drink the entire glass right there in front of the fridge. Then she’d walk into her room and stare at the TV for a little bit, listening to the weatherman deliver a forecast—more heat—she already knew.

Mom was beautiful but always on the edge of exhaustion. When she was in her twenties, she had worked briefly as a fashion model. Sometimes she’d let me look at pictures of her from those days, hair in box braids, her lithe frame draped in gowns her sister had designed, posing on runways. Even a long day of work couldn’t deny her the colors her black hair flashed, like raven feathers, when the light hit it just so. I was proud of her beauty, my first diva. Even as my body felt mangled by puberty, I took consolation in the fact that I came from a woman like her: a woman who read three newspapers every day, who could make everyone in a room light up with laughter, who would tuck notes into my lunch box daily, signing off, “I love you more than the air I breathe.”

After working at the airport all day, Mom was too tired for any of my questions, so I waited until she’d had a cigarette. After a smoke, she would be ready to talk.

She saw the Polaroid in my hand when I walked up to her. “I’d been wondering what happened to that.” She held the photo in her hand gently, as if it would crumble to dust if she wasn’t careful. Her face softened just a little.

“Who is he?” I asked.

She looked out the window at the oak tree right outside the living room. She stared at it long and hard, like she was waiting for some signal. Moments like this had taught me how to shut up and wait for an answer. When I was younger, I would give up during Mom’s pauses because I thought the answer wasn’t going to come. Eventually I learned that she was just testing me, to see how serious I was about finding out.

I stared at the window with her, then arched one eyebrow.

She sighed.

“A friend from school. We’d go on road trips together now and then. We went to Jackson once.”

She paused again, still looking at the tree. For a moment, it was quiet inside the apartment and out, like the heat was making the entire town hold its breath. Then Cody and Sam started yelling at each other in the parking lot.

Mom frowned and turned back to me.

“Not too long after that, he found out he was sick and… and he killed himself.”

She was already walking back to the kitchen for more water, which was her way of saying that the conversation was over. It was too hot, the day too long.

I wanted to see the man’s picture again. He had looked healthy to me. He was young, early twenties. And what did being sick have to do with killing yourself?

“Sick with what?” I called out, even as I felt bad for asking.

I had stepped into someone else’s house without their permission, but now that I was inside I couldn’t help looking around.

“AIDS,” she said.

She breezed into her bedroom and closed the door. I could hear her open a drawer and turn the TV on. I tried to listen for the weatherman’s predictions, but the volume was down too low.

I went back into my room and pulled Another Country out from under my pillow. After reading and rereading the same paragraph several times, I set the book back down.

AIDS, I thought. Shit.

She hadn’t even said her friend’s name.

“GAY” WASN’T A word I could imagine actually hearing my mom say out loud. If I pictured her moving her lips, “AIDS” came out instead. But in the days following our conversation about the photograph, I could feel the word “gay”—or maybe the word’s conspicuous absence—vibrating in the air between us.

I’d read in one of my nature books that there are some sounds that occur at a frequency only dogs and special radios can pick up on. Sounds that can only be heard if you were designed to hear them. I could hear that word ringing high above every conversation, every moment, because I thought about being gay all the time.

I heard it vibrating in the air when I watched Cody and his friends playing pickup in the park, sweat making their shirts transparent and heavy, their nipples poking at the fabric. I could hear it too when I thought about the man in the photograph. I wished I still had the Polaroid, but it would’ve been weird to ask Mom if I could look at it again. I wanted to see his smile; I thought I would understand it better now.

I carried that man’s smile in my head for three days until the smirk became a laugh, a taunt, a howl. One morning as Mom got ready to leave for work, I stared at the ceiling, then closed my eyes when she opened my bedroom door to let the dog in. Whenever she left, Kingsley would panic, pressing his face against the window so he could watch her car pull away. It happened five days a week; but each morning he was just as frantic, as if this would be the day she left, never to return.

With Kingsley yipping at my ankles, I ventured into Mom’s room. The picture wasn’t on her dresser and I thought about going through her drawers to find it. The last time I had done that, though, I’d found her vibrator. The discovery had been its own punishment.

Still, I knew that there was a place I could go to get the answers I wouldn’t find at home. Throwing on clothes without even eating, I opened the front door and locked it behind me. Kingsley barked and scratched at the sill as if he were trying to warn me.

IN THE PUBLIC library’s air-conditioned coolness, I decided I knew better than to ask the wrinkled woman at the circulation desk where to find books about being gay. Instead, I slowly walked up and down each aisle, scanning book spines until I found what I was looking for. The first book that stopped me was for parents dealing with gay children. The introduction was worded like it was intended for readers coping with a late-stage cancer diagnosis. I put the book back on the shelf, wrong side out.

Eventually, I gathered five or six books and sat down on the floor with them in my lap. Like any teenage boy trained at reading things he shouldn’t be, I looked both ways before opening any, then got up and grabbed a decoy off the shelf. It was a book about the “sociology of boys.” I kept it open on the second chapter and within reach in case someone I knew came down the aisle and I needed a quick alibi.

While I was reading a book about “defining homosexuality,” my dick started to get hard. The writing certainly wasn’t sexy; the language was outdated and dry. Still my body responded.

That changed as I read further into the books in my pile. All the books I found about being gay were also about AIDS. Gay men dying of AIDS like it was a logical sequence of events, a mathematical formula, or a life cycle. Caterpillar, cocoon, butterfly; gay boy, gay man, AIDS. It was certain. Mom’s friend got AIDS because he was gay. Because he was gay, he killed himself. Because he knew he was dying anyway.

I read about gay men who were abandoned by their families when they came out. Or worse, who didn’t tell anyone that they were gay, even when lesions started to blossom on their skin like awful flowers. Either way, the men in those books always seemed to die alone. I took some comfort in the fact that Mom knew about her friend’s illness. Maybe he had been able to tell the people close to him. Maybe Mom was the kind of person you could tell.

When I stood up to put the books back on the shelf, I realized my hands were shaking. I felt like I had made the mistake of asking a fortune-teller to look into my future, and now I was being punished for trying to look too far ahead. Walking outside, the blast of hot air was a relief.

I passed the park on the way home, and the usual boys were on the basketball court. Shirts and skins. I looked at their bodies, but only for a moment. I couldn’t really focus. In every man’s expression, shimmering amid the heat waves, I found myself searching for the face of the man in the photograph—for a hint of that smile, that beautiful, unforgivable smile.

Reading Group Guide

Join our mailing list! Get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Introduction

Haunted and haunting, How We Fight for Our Lives is a stunning coming-of-age memoir. Jones tells the story of a young, black, gay man from the South as he fights to carve out a place for himself, within his family, within his country, within his own hopes, desires, and fears. Through a series of vignettes that chart a course across the American landscape, Jones draws readers into his boyhood and adolescence—into tumultuous relationships with his family, into passing flings with lovers, friends, and strangers. Each piece builds into a larger examination of race and queerness, power and vulnerability, love and grief: a portrait of what we all do for one another—and to one another—as we fight to become ourselves.

An award-winning poet, Jones has developed a style that’s as beautiful as it is powerful—a voice that’s by turns a river, a blues, and a nightscape set ablaze. How We Fight for Our Lives is a one-of-a-kind memoir and a book that cements Saeed Jones as an essential writer for our time.

Topics & Questions for Discussion

1. Jones opens How We Fight for Our Lives with one of his poems, entitled “Elegy with Grown Folks’ Music” (Tin House, 2016). How does Jones see his mother in this poem? How does music change that view? Have you ever had a mundane experience that changed how you viewed your parents?

2. Why does Jones accompany Cody and Sam into the woods? What do we learn about Jones’s sexuality in this section, and how is that sexuality viewed by these neighbor boys? Do you think they understand the name they call him?

3. In the first few chapters, Jones learns that a friend of his mother’s committed suicide after being diagnosed with HIV/AIDS, and then he sits through a student performance of The Laramie Project. What does Jones take away from these portrayals of gay men in modern society?

4. Jones says that “just as some cultures have a hundred words for ‘snow,’ there should be a hundred words in our language for all the ways a black boy can lie awake at night” (24). What does Jones worry about as he’s coming of age? What do young black men have to fear in America today?

5. Jones’s mother is Buddhist and his grandmother is a devout Christian. How does religion influence his family dynamics?

6. After spending the summer with his grandmother, Jones realizes that “people don’t just happen. We sacrifice former versions of ourselves. We sacrifice the people who dared to raise us. The ‘I’ it seems doesn’t exist until we are able to say, ‘I am no longer yours.’” And he makes himself a promise: “Even if it meant becoming a stranger to my loved ones, even if it meant keeping secrets, I would have a life of my own (34–35).” Do you believe that you’ve had to sacrifice former versions of yourself? Have you ever felt like you were limited by your family’s impression of you? What did you have to do to change those impressions?

7. When Jones is deciding whether to meet a stranger in the library bathroom, he wonders about how the man views his body. Did the stranger mistake him for a grown man, “transformed, as the bodies of young black men are wont to do when stared at by white people in this country” (54)? Did he see him as the “exact body” that he wanted, or was he just “a body—no, a mouth” (55)? Later, he realizes that his body could be “a passport or a key, or maybe even a weapon” (68). Discuss the ways Jones views his body over the course of the book.

8. When he and his mother visit New York City during Pride Month and she points out a gay couple holding hands, Jones can’t tell if she’s being supportive or making fun of him—“In the absence of clarity, my worst anxieties reigned” (60). How well do you think you knew your parents when you were young? Are there parts of our parents we can’t know or access?

9. After Jones sees a drag show for the first time, he realizes that “that night was the first time in my life I felt like the words ‘gay’ and ‘alone’ weren’t synonyms for each other” (67). What do you think he means by this? Later, at a party in college, he notes that “my loneliness tended to drive me away from people like her [the only other black student at the party] and the gay couple, rather than toward them” (131). Why do you think Jones has trouble connecting with people who, on paper, are like him? Where are the places that Jones finds community in his adulthood?

10. When his mother is hospitalized for her heart condition, Jones says that “I could still see my mother fighting for her life” (74). In what ways is Jones’s mother fighting for her life? In what ways is she fighting for her son’s life? Jones uses this phrase later in the book when he recounts his experience with Daniel on New Year’s Eve (130; 134). What different meaning does this phrase take on when viewed in the context of male sexuality?

11. What does college represent to Jones? What promises did NYU hold for him, and what does WKU eventually provide?

12. As Jones is settling into his new life at WKU, he finds that he’s able to fit in with the boys on his floor and with his debate friends by accentuating different parts of his personality (86). How does he code-switch between these groups? What experiences did he have growing up that taught him how to do this effectively?

13. After Jones officially comes out to his mother, he writes that “I think I didn’t feel as if a burden had been lifted because my being gay was never actually the burden. There was still so much I hadn’t told my mother, so much I knew that I would probably never tell her. I had come out to my mother as a gay man, but within minutes, I realized I had not come out to her as myself” (97). What do you think he means by this? What’s the difference to Jones between coming out as gay and coming out as himself? Later he says that his mother and him are similar because they “both allowed too deep of a contrast between our interiors and our exteriors” (111). What is each hiding from the other?

14. Describe Jones’s relationship with the Botanist. Why do you think Jones and the Botanist are drawn to this arrangement? What does Jones learn from these encounters?

15. When Jones starts his teaching job after graduating from his master’s program, he writes that he was proud of his exhaustion because it was proof that he was “no longer just a son or grandson but an I,” separate from his family with his own life and career (148). When did you first feel like you were a grown-up? Did that change your relationship with your family?

Enhance Your Book Club

1. Read Jones’s debut poetry collection, Prelude to Bruise.

2. Consider reading some of the fiction writers that Jones read when he was a kid —Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, James Baldwin—or some of the poets he mentions that inspired him as an adult: Reginald Shephard, Melvin Dixon, Essex Hemphill, Joseph Beam, and Assotto Saint (4; 141).

3. When Jones is teaching in New Jersey, he recalls that his students were reading The Catcher in the Rye and that they loved Holden Caufield (148). Jones has said that How We Fight for Our Lives is the book he would’ve wanted to read when he was younger. Discuss with your book club what books spoke to you when you were younger. Are there any books you’ve read in your adult life that you wish you came across when you were younger?

4. For more information on Saeed Jones and How We Fight For Our Lives, visit https://www.readsaeedjones.com/.

Why We Love It

“An unforgettable coming-of-age story, of a bookish, black, gay teen from Texas as he learns to see himself and his dreams—and as he learns how his world sees him…and throughout, he reflects his nation back on itself, writing profoundly…with a gorgeous, intimate style that’s half-prose and half-poetry. It’s a book that takes your breath away, that you race through in a single sitting and then flip right back to page one.” —Jon C., Editor, on How We Fight for Our Lives

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (October 8, 2019)

- Length: 208 pages

- ISBN13: 9781501132735

Raves and Reviews

PRAISE FOR HOW WE FIGHT FOR OUR LIVES BY SAEED JONES

“[A] devastating memoir….Jones is fascinated by power (who has it, how and why we deploy it), but he seems equally interested in tenderness and frailty. We wound and save one another, we try our best, we leave too much unsaid….A moving, bracingly honest memoir that reads like fevered poetry.”—THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

"A raw and eloquent memoir. One could say that Saeed Jones' new memoir, How We Fight for Our Lives, is a classic coming-of-age story….But Jones' voice and sensibility are so distinct that he turns one of the oldest of literary genres inside out and upside down. How We Fight for Our Lives is at once explicitly raunchy, mean, nuanced, loving and melancholy. It's sometimes hard to read and harder to put down." —MAUREEN CORRIGAN, NPR'S "FRESH AIR"

"Extremely personal, emotionally gritty, and unabashedly honest, How We Fight for Our Lives is an outstanding memoir that somehow manages a perfect balance between love and violence, hope and hostility, transformation and resentment.....Jones writes with the confidence of a veteran novelist and the flare of an accomplished poet. This is an important coming-of-age story that's also a collection of tiny but significant joys. More importantly, it's a narrative that cements Jones as a new literary star — and a book that will give many an injection of hope."—NPR

“Urgent, immediate, matter of fact….The prose in Saeed Jones’s memoir How We Fight for Our Lives shines with a poet’s desire to give intellections the force of sense impressions.”—THE NEW YORKER

"Jones’ explosive and poetic memoir traces his coming-of-age as a black, queer, and Southern man in vignettes that heartbreakingly and rigorously explore the beauty of love, the weight of trauma, and the power of resilience."—ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY

"[Jones'] tenacious honesty compels us to be honest with ourselves. His experiences—negotiating grief, family dynamics, and a forthright identity—require our reckoning."—KIRKUS PRIZE 2019 CITATION

“[This] memoir marks the emergence of a major literary voice…written with masterful control of both style and material.” —KIRKUS REVIEWS (STARRED REVIEW)

“Powerful…Jones is a remarkable, unflinching storyteller, and his book is a rewarding page-turner.”—PUBLISHERS WEEKLY (STARRED REVIEW)

"An unforgettable memoir that pulls you in and doesn’t let go until the very last page."—LIBRARY JOURNAL (STARRED REVIEW)

"A luminous, clear-eyed excavation of how we learn to define ourselves, “How We Fight for Our Lives” is both a coming-of-age story and a rumination on love and loss....a radiant memoir that meditates on the many ways we belong to each other and the many ways we are released."—SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE

"There are moments of devastating ugliness and moments of ecstatic joy...infused with an emotional energy that only authenticity can provide."—MINNEAPOLIS STAR TRIBUNE

"Phenomenal....In this profound, concise memoir, the 33-year-old writer isolates key moments from his youth and sharpens their points for maximum effect. We follow a young, searching Jones through his early years with his loving single mother, along a path of unrequited lust, furtive sexual experiences, and disapproving relatives, through his hard-won self-acceptance and into the grief of losing the person closest to him."—INTERVIEW MAGAZINE

"Jones’ evocative prose has a layered effect, immersing readers in his state of mind, where gorgeous turns of phrase create some distance from his more painful memories. Although its length is short (just 189 pages), How We Fight For Our Lives fairly pulses with pain and potency; there is enough turmoil and poetry and determination in it to fill whole bookshelves."—THE AV CLUB

"How We Fight for Our Lives is a primer in how to keep kicking, in how to stay afloat...Thank god we get to be part of that world with Saeed Jones’ writing in it."—LAMBDA LITERARY

"Jones' unabashed honesty and gift for self-aware humor will resonate with readers, especially those in search of a story that resembles their own."

—BOOKLIST

“Scorching…a commentary not only on what it takes to become truly and wholly oneself, but on race and LGBTQ identity, power and vulnerability, and how relationships can make and break us along the way.”

—GOOD HOUSEKEEPING

“This memoir is a rhapsody in the truest sense of the word, fragments of epic poetry woven together so skillfully, so tenderly, so brutally, that you will find yourself aching in the way only masterful writing can make a person ache. How We Fight for Our Lives is that rare book that will show you what it means to be needful, to be strong, to be gloriously human and fighting for your life.”

—ROXANE GAY, author of Hunger

“This book. Oh my goodness. It is everything everyone needs right now—both love song and battle cry, brilliant as fuck and at times, heartbreaking as hell. Every single living half-grown and grownup body needs to read this book. I’m shook. I’m changed.”

—JACQUELINE WOODSON, author of Another Brooklyn

“There will be little left to say, and so much left to make after the world experiences Saeed Jones's How We Fight for Our Lives. This is that rare piece of literary art that teaches us how to read and write on every page. It's so black. So queer. So subtextual, and amazingly so sincere. Saeed changes everything we thought we knew about memoir writing, narrative structure, and heart meat. All three are obliterated. All three are tended to over and over again. All three will never ever be the same after this book. It's really that good.”

—KIESE LAYMON, author of Heavy

Awards and Honors

- Topaz Nonfiction Reading List (TX)

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): How We Fight for Our Lives Hardcover 9781501132735

- Author Photo (jpg): Saeed Jones Saeed Jones(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit