Get our latest book recommendations, author news, and competitions right to your inbox.

Table of Contents

About The Book

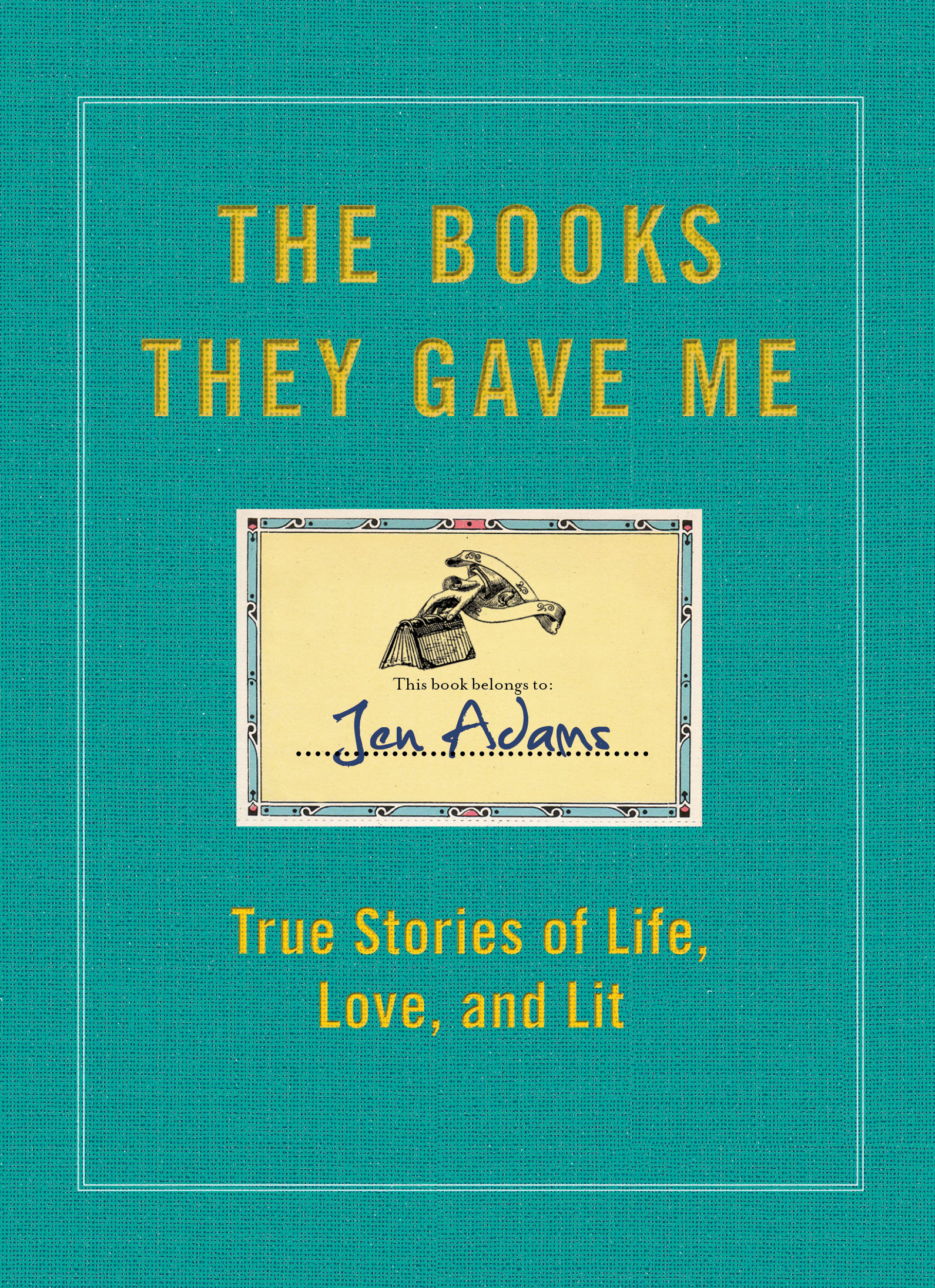

This beautiful full-color treasury of stories about gift book-giving celebrates the enduring power of literature: stories of significant books people have received and what those books mean to them.

THE GIFT OF A BOOK BECOMES PART OF THE STORY OF YOUR LIFE. Perhaps it came with a note as simple as “This made me think of you,” but it takes up residence in your heart and your home. The Books They Gave Me is a mixtape of stories behind books given and received. Some of the stories are poignant, some snarky, some romantic, some disastrous—but all are illuminating.

Jen Adams collected nearly two hundred of the most provocative stories submitted to the tumblr blog TheBooksTheyGaveMe.com to capture the many ways books can change our lives and loves, revealing volumes about the relationships that inspired the gifts. These stories are, by turns, romantic, cynical, funny, dark, and hopeful. There’s the poorly thought out gift of Lolita from a thirty-year-old man to a teenage girl. There’s the couple who tried to read Ulysses together over the course of their long-distance relationship and never finished it. There’s the girl whose school library wouldn’t allow her to check out Fahrenheit 451, but who received it at Christmas with the note, “Little Sister: Read everything you can. Subvert Authority! Love always, your big brother.” These are stories of people falling in love, regretting mistakes, and finding hope. Together they constitute a love letter to the book as physical object and inspiration.

Illustrated in full color with the jackets of beloved editions, The Books They Gave Me is, above all, an uplifting testament to the power of literature.

THE GIFT OF A BOOK BECOMES PART OF THE STORY OF YOUR LIFE. Perhaps it came with a note as simple as “This made me think of you,” but it takes up residence in your heart and your home. The Books They Gave Me is a mixtape of stories behind books given and received. Some of the stories are poignant, some snarky, some romantic, some disastrous—but all are illuminating.

Jen Adams collected nearly two hundred of the most provocative stories submitted to the tumblr blog TheBooksTheyGaveMe.com to capture the many ways books can change our lives and loves, revealing volumes about the relationships that inspired the gifts. These stories are, by turns, romantic, cynical, funny, dark, and hopeful. There’s the poorly thought out gift of Lolita from a thirty-year-old man to a teenage girl. There’s the couple who tried to read Ulysses together over the course of their long-distance relationship and never finished it. There’s the girl whose school library wouldn’t allow her to check out Fahrenheit 451, but who received it at Christmas with the note, “Little Sister: Read everything you can. Subvert Authority! Love always, your big brother.” These are stories of people falling in love, regretting mistakes, and finding hope. Together they constitute a love letter to the book as physical object and inspiration.

Illustrated in full color with the jackets of beloved editions, The Books They Gave Me is, above all, an uplifting testament to the power of literature.

Excerpt

INTRODUCTION

J. Alfred Prufrock measured his life out in coffee spoons. I measure mine out in pages. I am the archetypal bookworm, never without a book in my bag and four more in progress on my nightstand. My apartment is filled with books. In fact, when I was looking for a place here in New York, my primary requirement was that the apartment offered enough wall space to house all my bookcases. In short, books are my language, my vocabulary. Every experience in my life is filtered through what I’ve read and somehow processed in prose. I’m constantly reading and constantly writing. And anyone who knows me well must understand and accept this about me. The books are nonnegotiable. They are part of me. They are me.

So, when a man I was dating brought me an especially well-chosen book as a gift, I realized in a flash that, for those of us who live for the written word, books given and received in the context of a relationship can reveal so much. This observation is well documented in popular culture. In Woody Allen’s film Annie Hall, Annie and Alvy sort out their respective books as they are breaking up. Annie realizes that the relationship may have always been doomed—Alvy only ever gave her books with “death” in the title.

In one episode of the late 1980s TV series The Days and Nights of Molly Dodd, Molly’s ex-husband surprises her at work (in a bookshop, natch) one blustery cold night. Defensively, he says, “You know, I gave Molly some books once. Remember? Twenty-seventh birthday? Twenty-seven books.” Her current lover, bookshop owner Moss, appreciates this. “Books make nice gifts.” But Molly remembers well: “You gave me twenty-seven comic books, Frank. Not real books.” Frank failed the test, without even knowing he was taking one.

Sometimes, we put suitors to the test with full knowledge of what we are doing. In Martin Amis’s novel Money, Martina Twain gives the supplicant John Self a copy of Animal Farm, telling him that he needs to read it. He tries and fails, and never gets very far with Martina.

Books can also have potent influences over us; giving someone the right book at the right time can change his life forever—to wit, the little yellow-covered book Lord Henry Wotton gives to Dorian in Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. The suggestions of sensual excess in the book set Dorian off on a path that leads to corruption and utter ruin. More often, we hear of books that change lives for the better. In Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, Beth, Jo, and their sisters are each given a copy of The Pilgrim’s Progress as their only Christmas gift in a straitened, wartime year. The book becomes a spiritual guidebook as well as an imaginative one that will illuminate and shape their lives. And the effect of books on real people’s lives can be as powerful, as the stories in The Books They Gave Me will reveal.

At home, as I shelved my boyfriend’s gift book, I touched the spines of other books I’d been given by men I’d loved. The beautiful hardcover edition of the complete poems of William Blake. A picture book, a tongue-in-cheek response to the rise of the e-book. A slim little paperback reprint of lyric poetry. Each of them, I realized, said something important about who we were at that moment. The books I own tell my life story, and the ones given me by the people I love offer special insight into the experiences that have made me who I am.

I began to collect stories of gifted books, and decided to compile them in that most modern of diaristic forms, the blog. Stories began to pour in to TheBooksTheyGaveMe.com from all over the world as word spread and other readers decided to share their experiences. Some are wryly funny; some will make you cry or ball your fists in anger. I began saving the best of them, having realized that a book compiling these stories is one that I’d love to read and own.

I’ve been moved profoundly by my readers’ submissions. They’ve told me of their loves, those they lost and those they’re lucky enough to be with. Their books are an important part of their identities and their personal histories. There’s something magical about this blog and the reaction to it—it is causing people to look at their shelves—and at the habit of owning, sharing, and giving books—with new eyes.

In this age of the e-book, part of the appeal of being given a hard copy book as a gift is its tangible timelessness. Books are real. You can give a book as a gift. Kindles are great for reading on the subway, and they get people to read more than they might otherwise, but they are flatly unromantic. Paper books offer a kind of permanent charm. They don’t expire; they can’t disappear in a power surge. Books last. I’m not with any of those men anymore, but I still have the books they gave me.

J. Alfred Prufrock measured his life out in coffee spoons. I measure mine out in pages. I am the archetypal bookworm, never without a book in my bag and four more in progress on my nightstand. My apartment is filled with books. In fact, when I was looking for a place here in New York, my primary requirement was that the apartment offered enough wall space to house all my bookcases. In short, books are my language, my vocabulary. Every experience in my life is filtered through what I’ve read and somehow processed in prose. I’m constantly reading and constantly writing. And anyone who knows me well must understand and accept this about me. The books are nonnegotiable. They are part of me. They are me.

So, when a man I was dating brought me an especially well-chosen book as a gift, I realized in a flash that, for those of us who live for the written word, books given and received in the context of a relationship can reveal so much. This observation is well documented in popular culture. In Woody Allen’s film Annie Hall, Annie and Alvy sort out their respective books as they are breaking up. Annie realizes that the relationship may have always been doomed—Alvy only ever gave her books with “death” in the title.

In one episode of the late 1980s TV series The Days and Nights of Molly Dodd, Molly’s ex-husband surprises her at work (in a bookshop, natch) one blustery cold night. Defensively, he says, “You know, I gave Molly some books once. Remember? Twenty-seventh birthday? Twenty-seven books.” Her current lover, bookshop owner Moss, appreciates this. “Books make nice gifts.” But Molly remembers well: “You gave me twenty-seven comic books, Frank. Not real books.” Frank failed the test, without even knowing he was taking one.

Sometimes, we put suitors to the test with full knowledge of what we are doing. In Martin Amis’s novel Money, Martina Twain gives the supplicant John Self a copy of Animal Farm, telling him that he needs to read it. He tries and fails, and never gets very far with Martina.

Books can also have potent influences over us; giving someone the right book at the right time can change his life forever—to wit, the little yellow-covered book Lord Henry Wotton gives to Dorian in Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. The suggestions of sensual excess in the book set Dorian off on a path that leads to corruption and utter ruin. More often, we hear of books that change lives for the better. In Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, Beth, Jo, and their sisters are each given a copy of The Pilgrim’s Progress as their only Christmas gift in a straitened, wartime year. The book becomes a spiritual guidebook as well as an imaginative one that will illuminate and shape their lives. And the effect of books on real people’s lives can be as powerful, as the stories in The Books They Gave Me will reveal.

At home, as I shelved my boyfriend’s gift book, I touched the spines of other books I’d been given by men I’d loved. The beautiful hardcover edition of the complete poems of William Blake. A picture book, a tongue-in-cheek response to the rise of the e-book. A slim little paperback reprint of lyric poetry. Each of them, I realized, said something important about who we were at that moment. The books I own tell my life story, and the ones given me by the people I love offer special insight into the experiences that have made me who I am.

I began to collect stories of gifted books, and decided to compile them in that most modern of diaristic forms, the blog. Stories began to pour in to TheBooksTheyGaveMe.com from all over the world as word spread and other readers decided to share their experiences. Some are wryly funny; some will make you cry or ball your fists in anger. I began saving the best of them, having realized that a book compiling these stories is one that I’d love to read and own.

I’ve been moved profoundly by my readers’ submissions. They’ve told me of their loves, those they lost and those they’re lucky enough to be with. Their books are an important part of their identities and their personal histories. There’s something magical about this blog and the reaction to it—it is causing people to look at their shelves—and at the habit of owning, sharing, and giving books—with new eyes.

In this age of the e-book, part of the appeal of being given a hard copy book as a gift is its tangible timelessness. Books are real. You can give a book as a gift. Kindles are great for reading on the subway, and they get people to read more than they might otherwise, but they are flatly unromantic. Paper books offer a kind of permanent charm. They don’t expire; they can’t disappear in a power surge. Books last. I’m not with any of those men anymore, but I still have the books they gave me.

Product Details

- Publisher: Atria Books (February 24, 2015)

- Length: 256 pages

- ISBN13: 9781451688795

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Books They Gave Me Paper Over Board 9781451688795(5.5 MB)